2009: Taking A Bite Out Of Water Use

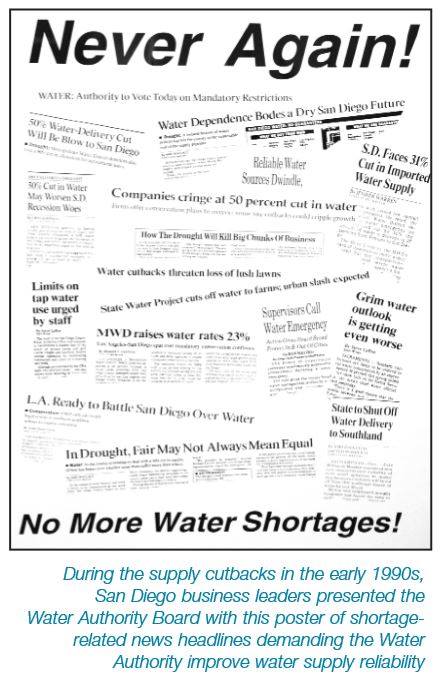

Ten years ago, the state and region were facing a water crisis — snowpack levels were below normal and water restrictions were in place.

Thinking outside the box, the Water Authority sweetened its conservation outreach efforts by partnering with the San Diego-Imperial Council of the Girl Scouts to distribute water conservation tip sheets across the region with the scouts’ popular cookies.

In March 2009, 400,000 conservation cards were handed out with 2 million boxes of cookies. “Please take a few moments to implement one or more saving tips,” the cards said. “The amount of water saved could have a huge impact on our region!”

This partnership was part of a $1.8 million outreach program that helped the San Diego region prepare for potential water supply allocations. The campaign was the Water Authority’s largest advertising and marketing effort since the early 1990s.