As the planet warms, scientists expect that mountain snowpack should melt progressively earlier in the year. However, observations in the U.S. show that as temperatures have risen, snowpack melt is relatively unaffected in some regions while others can experience snowpack melt a month earlier in the year.

This discrepancy in the timing of snowpack disappearance—the date in the spring when all the winter snow has melted—is the focus of new research by scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

In a new study published March 1 in the journal Nature Climate Change, Scripps Oceanography climate scientists Amato Evan and Ian Eisenman identify regional variations in snowpack melt as temperatures increase, and they present a theory that explains which mountain snowpacks worldwide are most “at-risk” from climate change. The study was funded by NOAA’s Climate Program Office.

Mountain snowpack changing rapidly in coastal regions

Looking at nearly four decades of observations in the Western U.S., the researchers found that as temperatures rise, the timing of snowpack disappearance is changing most rapidly in coastal regions and the south, with smaller changes in the northern interior of the country. This means that snowpack in the Sierra Nevada, the Cascades, and the mountains of southern Arizona is much more vulnerable to rising temperatures than snowpack found in places like the Rockies or the mountains of Utah.

The scientists used these historical observations to create a new model for understanding why the timing of snowpack disappearance differs widely across mountain regions. They theorize that changes in the amount of time that snow can accumulate and the amount of time the surface is covered with snow during the year are the critical reasons why some regions are more vulnerable to snowpack melt than others.

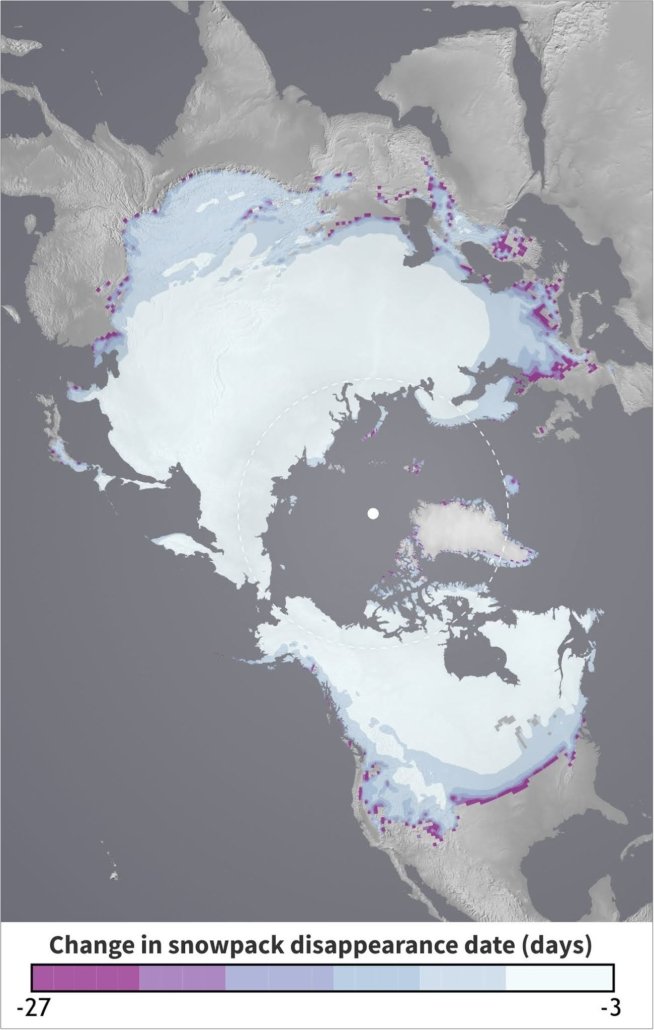

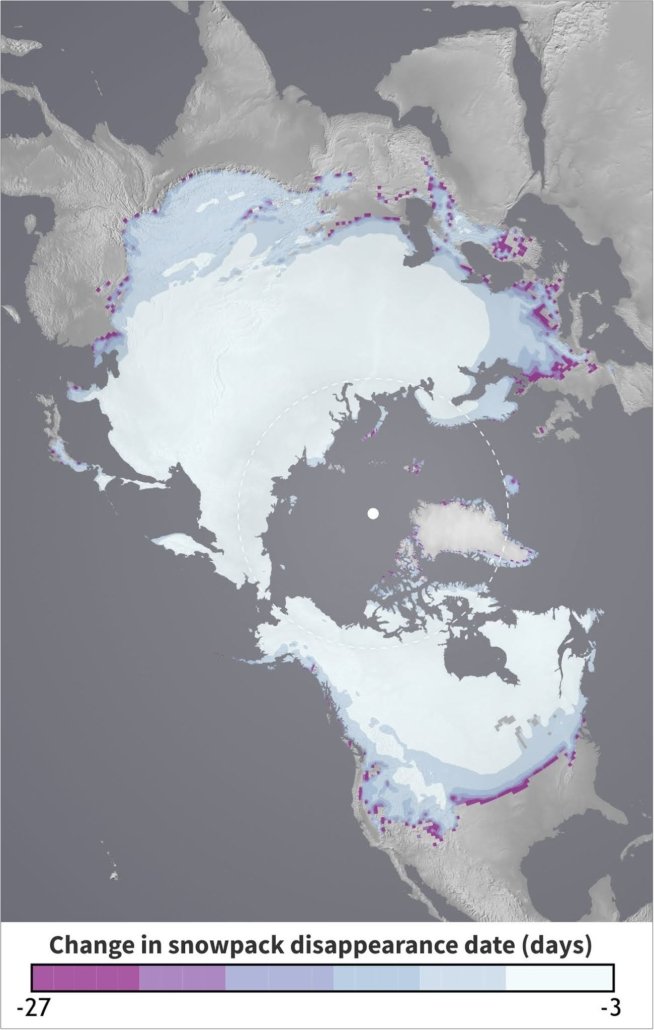

Using a new model, the Scripps researchers theorize that snowpack in coastal regions, the Arctic, and the Western U.S. may be among the most at-risk for premature melt from rising temperatures. Graphic: Courtesy Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Snowpack vulnerable due to increasing temperature

“Global warming isn’t affecting everywhere the same. As you get closer to the ocean or further south in the U.S., the snowpack is more vulnerable, or more at-risk, due to increasing temperature, whereas in the interior of the continent, the snowpack seems much more impervious, or resilient to rising temperatures,” said Evan, lead author of the study. “Our theory tells us why that’s happening, and it’s basically showing that spring is coming a lot earlier in the year if you’re in Oregon, California, Washington, and down south, but not if you’re in Colorado or Utah.”

Applying this theory globally, the researchers found that increasing temperatures would affect the timing of snowpack melt most prominently in the Arctic, the Alps of Europe, and the southern region of South America, with much smaller changes in the northern interiors of Europe and Asia, including the central region of Russia.

Climate Change and snowmelt

To devise the model that led to these findings, Evan and Eisenman analyzed daily snowpack measurements from nearly 400 sites across the Western U.S managed by the Natural Resources Conservation Service Snowpack Telemetry (SNOTEL) network. They looked at SNOTEL data each year from 1982 to 2018 and focused on changes in the date of snowpack disappearance in the spring. They also examined data from the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR) showing the daily mean surface air temperature and precipitation over the same years for each of these stations.

Using an approach based on physics and mathematics, the model simulates the timing of snowpack accumulation and snowpack melting as a function of temperature. The scientists could then use the model to solve for the key factor that was causing the differences in snowpack warming: time. Specifically, they looked at the amount of time snow can accumulate and the amount of time the surface is covered with snow.

“I was excited by the simplicity of the explanation that we ultimately arrived at,” said Eisenman. “Our theoretical model provides a mechanism to explain why the observed snowmelt dates change so much more at some locations than at others, and it also predicts how snowmelt dates will change in the future under further warming.”

A “shrinking winter” and longer fire season

The model shows that regions with very large swings in temperature between the winter and summer are less susceptible to warming than those where the change in temperature from winter to summer is smaller. The model also shows that regions where the annual mean temperature is closest to 0˚C are less susceptible to early melt. The most susceptible regions are ones where the differences between wintertime and summertime temperatures are small, and where the average temperature is either far above, or even far below 0˚C.

For example, in an interior mountain region of the U.S. like the Colorado Rockies, where the temperature dips below 0°C for about half the year, an increase of 1°C can lead to a quicker melt by a couple of days—not a huge difference.

However, in a coastal region like the Pacific Northwest, the influence of the ocean and thermal regulation helps keep the winter temperatures a bit warmer, meaning there are fewer days below 0°C in which snow can accumulate. The researchers hypothesize that in the region’s Cascade Mountains, a 1°C increase in temperature could result in the snow melting about a month earlier in the season—a dramatic difference.

Arctic “at risk”

One of the most “at-risk” regions is the Arctic, where snow accumulates for nine months each year and takes about three months to melt. The model suggests that 1°C warming there would result in a faster melt by about a week—a significant period of time for one of the fastest warming places on Earth.

This study builds upon previous work done by Scripps scientists since the mid-1990s to map out changes in snowmelt timing and snowpacks across the Western U.S. The authors said that a “shrinking” winter—one that is shorter, warmer, and with less overall precipitation—has adverse societal effects because it contributes to a longer fire season. This could have devastating impacts on already fire-prone regions. In California, faster snowpack melt rates have already made forest management more difficult and provided prime conditions for invasive species like the bark beetle to thrive.

Funding for this work was provided by a NOAA/CPO grant to the University of California.